Design for Our Lives - Quantified

Getting to Zero - State of Place Style!

Wow, what an interesting 6+ months it’s been! In May, we launched our Design for our Lives blog series, exploring the role that urban design was playing - or not - in Vision Zero strategies aiming to eliminate road collisions, injuries, and fatalities. After analyzing how 35 U.S. cities were tackling this honorable aim - and noting that design was sadly, decidedly, not a significant part of most cities action plans, we got the opportunity to work with the City of Durham, as part of their Innovate Durham program, to tie the built environment (as measured by State of Place) to safety, to help cities - like Durham - implement a more data-driven, and more holistic approach to “Get to Zero.” Yesterday, on Demo Day, 12 weeks after the inception of the program, Devin Nieusma, our Customer Development Intern, presented our work to various municipal departments from the City of Durham. TLDR; Design matters - quite simply, intersections in which people have lost their lives are just not designed to keep pedestrians, cyclists, and even motorists, safe - period. But we encourage you to dig deeper into our results, which shows the odds and probabilities of collisions based on the quality of urban design, as measured by State of Place.

All about that data

State of Place trained four community members to collect over 290 urban design features for a sample of blocks across the City of Durham's existing hotspots (areas where there have historically been a high concentration of traffic collisions) to get an initial baseline of existing walkability (State of Place Index) as well as the current built environment assets and needs (State of Place Profile).

Specifically, we extracted the Walk Scores for each the City of Durham’s 376 hotspots, and grouped them into five levels of “performance” along this proxy for walkability, based on the hotspots’ average and standard deviation. We then sampled a random - proportionate - number of hotspots from each level, totalling to 60 total hotspots. We then mapped out all blocks (the area between two intersections) that were adjacent to each of the hotposts. Together, this amounted to 372 total blocks for which we - including Durham community members - collected State of Place data (see map below). A special shout out to our super-human data collector, Dan, for collecting the most data out of our community volunteers - he collected data for 77 blocks!

A Poor Place Diagnosis…BUT

Overall, the City of Durham’s hotspots need a lot of urban design TLC…with an average State of Place Index of 29.4, they are (statistically) below that of the average State of Place Index (based on our database of nearly 8000 blocks) of 35.6.

Average State of Place Index & Profile

Average State of Place Index & Profile of sample of Durham, NC’s collision sites from 2012-2016

Average State of Place Index & Profile of sample of Durham, NC’s collision sites + adjacent blocks

Taking into account blocks adjacent to the hotspots, the State of Place Index of 28.2 is even lower than that of the average of the blocks in which the collisions occurred. This tells cities they need not only address urban design issues of collision sites, but must also improve the built environment of surrounding blocks. In fact, the very definition of the term hotspot should be expanded to include adjacent blocks.

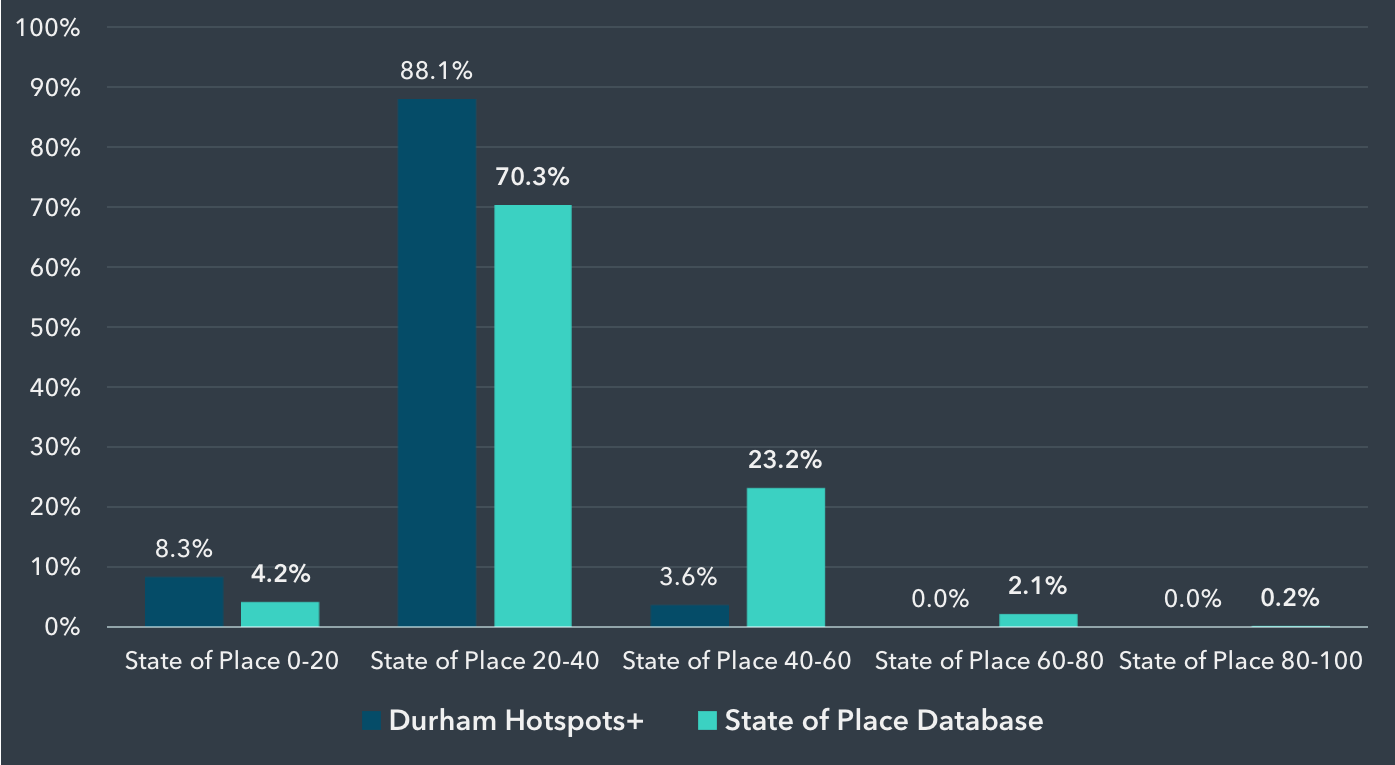

Now, you might be thinking, geez, the average State of Place Index of 35.6 is pretty low to begin with. We tend to agree - but this just highlights the fact that U.S. cities (of which our database is mostly comprised) need a lot of TLC, period. But we should also point out that unlike other scoring systems, State of Place is not based on a “ranking” but rather on “performance” - so it’s actually pretty hard to get a score of 100, or even 90. In fact, below, you can see how our database “stacks up” across five levels of the State of Place Index. As you can see, just over 2% of the entire database scores over 60! That said, when you compare the overall State of Place database to that of Durham’s hotspots, you can see that the City’s unsafe blocks are decidedly over-represented at the lower levels. That is, nearly 90% of Durham’s hotspots (we’ll use this term to refer to the collision sites and their adjacent blocks moving forward) score between a 20 and 40 on the State of Place Index as compared to just over 70% in the database; nearly twice as many score in the lowest level of State of Place; only 3.6% score between a 40-60; and none of them score over 60, period. There is no doubt that Durham’s hotspots are not just poorly designed, they are some of the most poorly designed streets across our 248 neighborhoods for which State of Place currently has data (which in and of itself is a microcosm of the typical walkability across most U.S metro regions).

Bottom line, the design of these hotspots is decidedly not pedestrian or bike friendly. But now what? How much of the reason that these collisions occurred is due to urban design in the first place? Can it be a coincidence? Could it be that most of Durham blocks are similarly designed and these are just where these tragic incidents happen to occur? Well, that is exactly what we wanted to know - and tested - using a technique called logistic regression that will help us understand how urban design impacts the odds and probability of a collision occurring.

A promising place Prognosis

After comparing the State of Place Index of the hotspots (collisions plus adjacent blocks) to a random sample of blocks from our database, we found that for every one point increase in the State of Place Index, the odds of a collision decrease by 12.3% on average. And as you can see below, the impact of design on the probability of a collision is much more “pronounced” the lower your baseline score is. That means that even a relatively small improvement on the State of Place Index - which can be achieved by doing fixes as simple as adding sidewalks, curb cuts, and crosswalk markings - can have a HUGE impact on saving lives.

We went deeper into our analysis to understand how the ten urban design dimensions that make up the State of Place Index “factor” into street safety. Turns out the that presence, quality, and access to parks and public spaces has a very high impact on the odds of a collision - in a good way, as do pedestrian safety, traffic safety, density, and form. Specifically, a one point increase in these dimensions reduced the odds of a collision as per the chart below:

On the flip side, a one point decrease in perceived crime safety and proximity to non-residential locations increased the odds of a collision by 12.8% and 3.7%, respectively. The tie-in to perceived safety has a very important implication from an safety perspective, as it indicates that areas in which people feel less safe - personally - are also areas in which the odds of a collision are higher, once again signaling the inherently unequal access to safer places overall.

Design for - all - our lives, NOW!!

Bottom line, design matters for all of us - and in particular for those most vulnerable among us. And most importantly, we have finally, without question, quantified that design is literally a matter of life and death…Twenty people lost their lives in the hotspots for which we collected data - 16 of these were pedestrians and bicyclists. Cities must absolutely stop playing with people’s actual lives - they must stop just “intuiting” what design changes matter or simply copying and pasting what other communities have or are doing. We now have data that 1) shows which hotspots need the most attention; 2) shows what’s working and what’s mostly not; 3) identifies which specific changes to make that will make the most impact - or reduce the probability of someone dying at the hands of a city; and even 4) have data that shows the dollars and cents behind it (if you still need that to justify the changes). Quite simply, there is no excuse NOT to use this data, like yesterday. Cities can access this data via an easy (and may we add - fun) to use software, to create effective, cost-efficient projects, quickly and affordably. No brainer - but just in case you have an inkling of doubt, the week after next, we’ll show you exactly how we could increase the State of Place Index of one of Durham’s collision sites from a 28.2 to a 74, or more significantly, reduced the probability of future collisions on that intersection from 60.8% to .74%. In the meantime, we invite you to join us - let’s all work together to DESIGN FOR -ALL- OUR LIVES…

If you want to walk with us on the path to Zero or learn more about the work we did for Durham as part of the Innovate Durham competition, feel free to request a time to chat and/or take our software for a test walk!

Also, HUGE shout out to Dr. Elizabeth Shulman, who helped me brush off my logistic regression skills and interpret the results of these analyses in the most “lay-friendly,” translate-straight-into-design-and-policy-ready language possible! Gotta love #anteater life (inside joke - go UCIrvine!).