Build It and They Might Come...

Why the Path to a Vibrant City is Not Merely Walkable

Hello fellow data-geeks and place-oholics! We're still laser focused on preparing our Phase II Small Business Innovation Research grant proposal due at the end of this month (wish us luck) to help make State of Place even better! So we're continuing our Best Ofs through the end of February!

Today, we open up with another topical conversation (especially given the state of our political discourse): the importance of nuance and how glossing over them can lead us to create false equivalencies and/or overstep, both in terms of promises we make or fears we spur. I wrote about this several years ago when walkability was just starting to hit the mainstream (good) but it was being offered as a panacea for all city problems (not good). But as with politics, the devil's in the details...Hope you enjoy our discussion about what to expect - and what not to - from the built environment in our quest to make cities more healthy, livable, and sustainable.

It’s no secret that I’m an avid proponent of “good” urban design, walkability, and dynamic cities. I’ve bemoaned my hometown, Miami’s lack of those elements loudly and repeatedly (see my rant about the bright blue Public Storage building at the corner of my mom’s block). Ah, poor “Weh-ches-teh” (Miami Cuban for “Westchester”); sigh, “Me-ya-me” (ditto, “Miami”). So the fact that ever more planners, government officials, developers, and investors have begun to consider the role of the built environment in economic development and to understand that the State of Place Index impacts a city’s success is reassuring.

Interest in Walkability by State

Not long ago, we urban design “geeks,” pedestrian advocates, and active-living proponents were the only people using urban-design terms such as “walkability.” Today, my Google News “walkability” search returns several articles daily, from publications like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Economist to US News & World Report, USA Today, and the Huffington Post. Google Trends return a stable number of requests for walkability in the last five years, too.

Google Trends show steady number of searches for 'walkability'

Twitter hashtags – #walkable and #walkability – yield countless tweets, from the businessman looking for #walkable restaurants near his hotel, to the realtor boasting how many listings she has in #walkable neighborhoods, to the latest study showcasing the benefits of #walkability.

The idea of, desire for, and benefits of walkability – living within a safe, comfortable, and pleasant walk of basic amenities – has hit the mainstream.

All good news … except that walkability was accused of approaching “buzzword” status (see, for example, here, here, and here). This is a fate I never would have predicted given the blank stares and perplexed shrugs I got from my Miami friends and family when I told them 16 years ago that I was moving 3,000 miles away to study urban design, behavior, and walkability.

For more than fifteen years, I’ve worked tirelessly to identify the empirical links between urban design and walkability and to guide evidence-based policy and practice that makes healthy, sustainable, and thriving environments possible. As much as it’s great that more people “get it,” the last thing I want is for the meaning of “walkability” to degenerate into fluff.

More concerning: the risk that city planners, policymakers, and stakeholders will look to “walkability” as a “cure-all” for city ills. In other words, I fear we are dangerously close to “environmental determinist” thinking – or the idea that X built environment intervention creates Y impact (be it economic, environmental, health, or otherwise). I cover environmental determinism in the first or second lecture of my urban-design class and like to use my riff on the Field of Dreams metaphor to explain the concept: It’s not “build it and they (actually, it's he, but you know what I mean) will come,” but rather build it and they might come.

Photo courtesy of WalkArlington

As much as it behooves me as an entrepreneur to extol the benefits of walkability and good urban design, the built environment can only do so much. Many factors influence “Y” besides just the built environment, including individual preferences, attitudes, and behaviors; societal norms; the global economy; geography, climate and topography, and more. Not to mention that the city is faced with numerous other “Ys” – issues including poverty, inequity, crime, disinvestment, unemployment – that cannot be addressed by the built environment alone.

To give a concrete example of the complex relationship between the built environment and behavior (including economic “behavior”), take the case of one of our past customers, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, which used the State of Place Index to inform their strategic investment plan for the D.C. metro region.

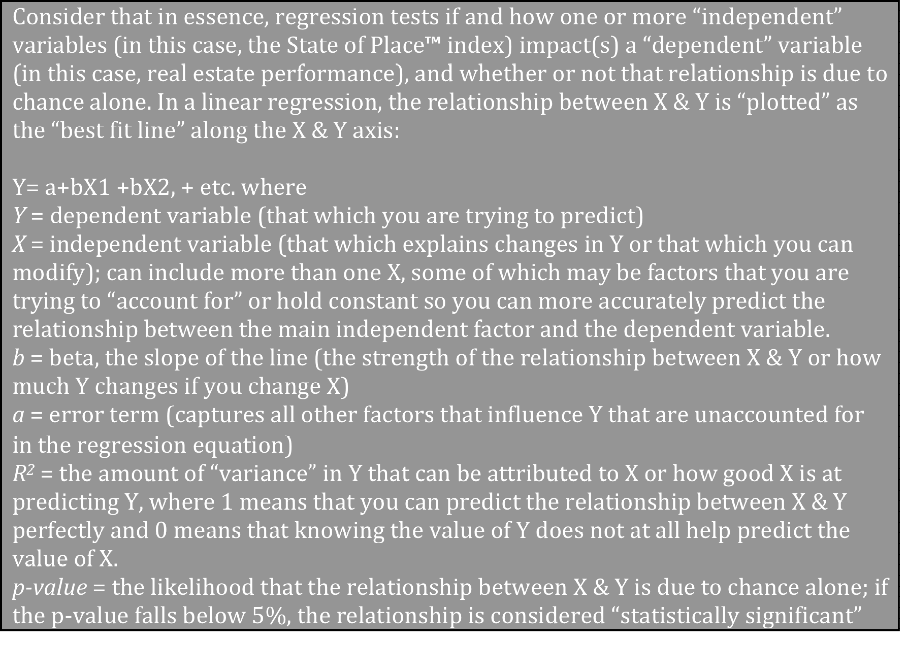

During one of our many (very data geeky discussions), I was reviewing the results of a regression analysis of the relationship between State of Place and various real estate performance indicators. Failing to reign in my inner academic, I launched into a conversation about R2 (R squares) and betas, causality and correlation, and effect sizes and p-values. I explained that while the built environment (“Y”, as measured by the State of Place index) does impact economic performance (“X1”), that relationship is influenced by a host of other factors (captured in “a”), some of which – for the purposes of this analysis – we “controlled” (like household income “X2”) and some of which we did not (like individual preferences regarding place types, a place’s “brand,” its location in the region, etc.)

So When You Build It, What Might Come?

- For example, in the case of the Metro DC region, take the difference between office rents in Tysons Corner and those in Silver Spring - the difference in office premiums is due to their State of Place Index (built environment). In fact, 47.4% (that is the R2) of the difference in their office rents is attributable to their State of Place Index. This means more than simply saying that the built environment and economic performance are correlated; the former can be used to predict the latter. However, there are other factors that also account for why office rents in Tysons differ from those in Silver Spring (that is the remaining 52.6% of the variance).

- The magnitude of this relationship is strong (based on the R2) meaning that the predictive value of the State of Place Index is high – it’s a sound indicator of economic performance.

- A one-point increase in the State of Place Index is linked to a $0.334 increase in office rents and a $0.283 increase in retail rents (that is based on b, the Beta score).

- This relationship is not due to chance (that is the p-value).

- This relationship is not simply due to these places’ average household incomes (we have “accounted” for X2, the “control”)

- We cannot say that X causes Y (causality cannot be established based on this statistical analysis because we have not measured the impact over time as well as due to other factors such as the research design).

The bottom line is that while:

- Walkability, as measured by State of Place, is an important factor in a community’s economic performance

- Increasing the State of Place Index can facilitate economic development, and

- Using State of Place, one can reasonably predict the return on investment of built environment interventions, which helps to guide policy and practice.

We must also consider that:

- Concerted policy, planning, and urban design efforts leading to built environment interventions and investments that bolster a community’s State of Place and address relevant regional and local factors can enhance that community’s triple bottom line.

And while moving forward:

- We can quantify the impact of our interventions and investments (by collecting before and after data) to better understand the relationship between State of Place and economic development, as well as other factors.

We cannot assume that:

- If we improve Tysons’ State of Place Index by X, it will automatically lead to increases in Y.

Ultimately, while I am encouraged by the enthusiasm around walkability and the increased acceptance of the built environment’s contribution to the triple bottom line (believe me, my life’s work has focused around understanding this relationship), it is important to be wary of anything labeled a panacea for all city problems.

As Jane Jacobs poignantly pointed out in her classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, you cannot just plan your way into a utopian ideal; cities are messy, organic, dynamic. And predicting what factors will impact cities and human behavior – and to what extent – is complicated!

Tools like State of Place must be part of a holistic, concerted effort to improve communities’ quality of life. We can indeed tell you what's working and what's not from a built environment perspective, help you figure out the changes you can make that are most likely to boost walkability and economic development, and even forecast the estimated economic benefits you'd get from those improvements - there's not doubt. But while walkability is certainly an urban-design ideal to strive toward for multiple reasons across the triple bottom line, it's critical to remember that the path toward a livable, sustainable, thriving city is not merely a walkable one.

So now that you know what to realistically expect from walkability, we'd love to show you the best way to cost-effectively make your community more walkable and livable AND provide you with a more effective way to advocate for your walkable development projects and plans - just like we did for the City of Tigard. Think less time, money and agony - and all the reward (just short of a panacea, of course)! Please contact us to find out how we can help you make the case for for walkable places!